SPACE July 2025 (No. 692)

Exterior view of the Korean Pavilion. Photo by Choi Yongjoon / ©Korean Pavilion 2025

The Korean Pavilion’s opening ceremony on May 9. Image courtesy of Arts Council Korea / ©Choi Jinbo

‘Intelligens. Natural. Artificial. Collective.’: 2025 Venice Biennale | Korean Pavilion

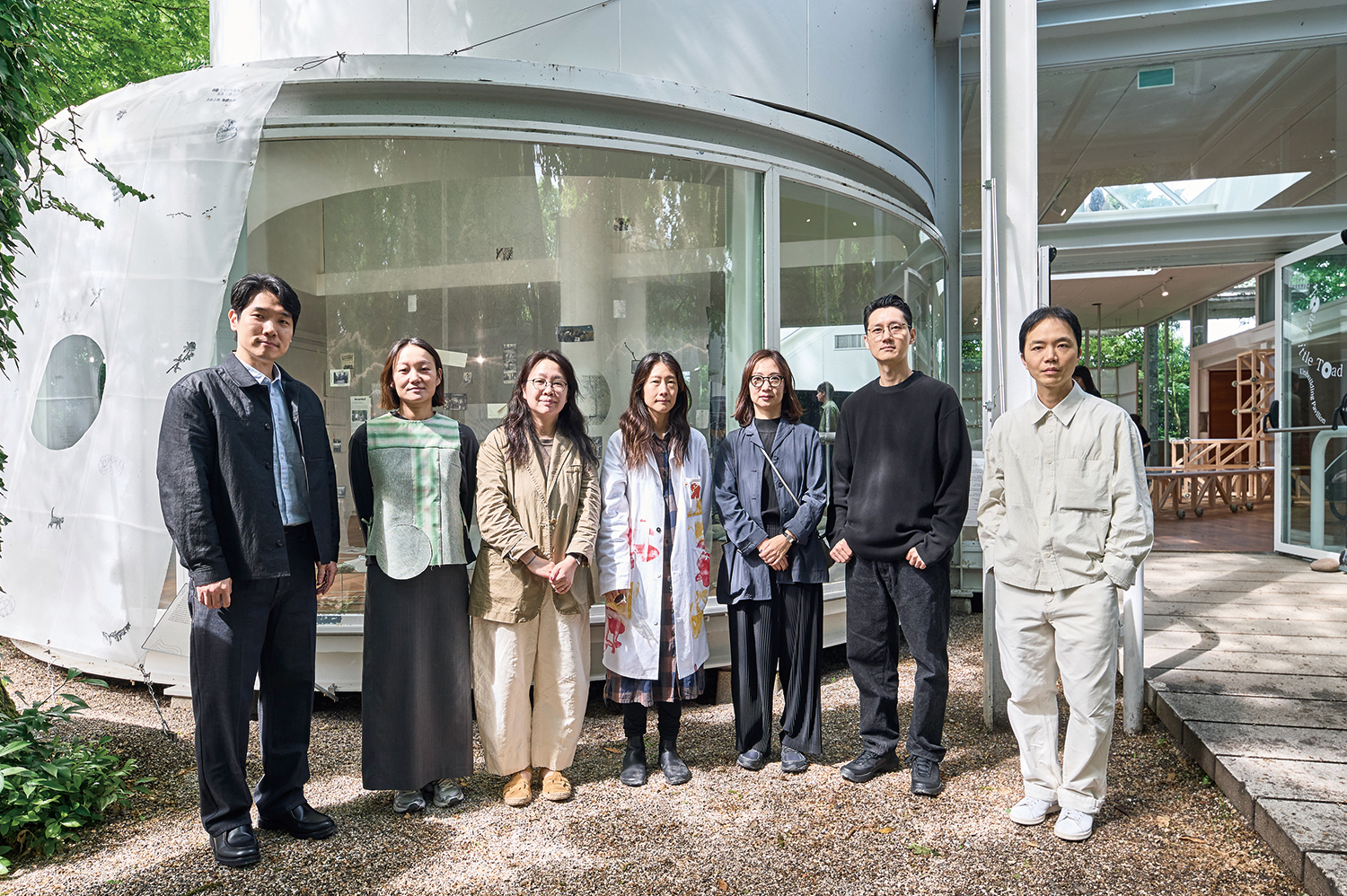

Ahead of the official opening of the Venice Biennale, Giardini buzzes with activity during its three-day pre-opening period as national pavilions open and visitors hurriedly explore the newly unveiled expansive exhibitions, exchanging impressions. At the Korean Pavilion’s opening ceremony on the 9th of May and the subsequent special architectural forum commemorating its 30th anniversary – ‘Vision & Legacy: 30 Years of the Korean Pavilion’ – former commissioners and curators, were joined by an unusually large number of domestic and international architects and art professionals, creating a packed and vibrant event. CAC, the curator of the Korean Pavilion this year, through the exhibition ‘Little Toad Little Toad: Unbuilding Pavilion’ call on us, paradoxically beyond national borders, to rethink the history and meaning of the Korean Pavilion, which first set anchor in the Giardini thirty years ago.

Exhibition view of ‘Little Toad Little Toad: Unbuilding Pavilion’. Photo by Choi Yongjoon / ©Korean Pavilion 2025

The Korean Pavilion has always been treated like a black sheep. With an architectural footprint of just over 240m², this small pavilion – irregular in its plan and virtually transparent – has long been considered a challenging venue for exhibitions, both in terms of the biennial art exhibitions and the architecture biennales held biennially. Since its completion in 1995, hosting 15 art exhibitions and 13 architecture exhibitions, its transparent glass walls have repeatedly been obscured in various ways, even attaching installations to the exterior to assert its presence between the German and Japanese Pavilions. Genuine efforts to imagine the Pavilion as more than a mere backdrop only gained momentum in 2023 when Franco Mancuso, co-architect of the Pavilion, donated some 4,000 documents related to its construction to the ARKO Arts Archive.

Unlike previous editions, mostly led by architects as curators, this year’s 14th architecture exhibition at the Korean Pavilion is overseen by CAC (co-directors, Chung Dahyoung, Kim Heejung, Jung Sungkyu), a team of architectural curators. Also part of the curatorial team for the 2018 exhibition ‘Spectres of the State Avant-garde’, they have continued to explore museums and archives through workshops, exhibitions, and forums. Having sought to uncover new qualities of place in 2018, it was natural for them – on the 30th anniversary – to make the Pavilion’s architecture itself the centrepiece. Drawing on Franco Mancuso’s donated materials and other scattered records, the curators reveal the geopolitical context of Giardini and Venice that shaped the Pavilion’s physical characteristics. They also overlay sensory layers of the architectural conditions and spatial qualities through commissioned works by Kim Hyunjong (principal, ATELIER KHJ), Park Heechan (principal, Studio Heech), Young Yena (co-principal, Plastique Fantastique), Lee Dammy (principal, Flora and Fauna). Additionally, as a unifying concept of the exhibition, they invoked the toad, main character of an old house-building song—sung while playing in the soil.

Overwriting, Overriding by Lee Dammy. Photo by Choi Yongjoon / ©Korean Pavilion 2025

The curators sought to care for the building, by marking the boundaries between inside and outside and naming the often-overlooked elements throughout the space. ©Kim Jeoungeun

Curators’ Perspective: House and Care

This exhibition begins outside the Korean Pavilion. The curators sought to care for the building, co-designed by the late Kim Seok Chul and Franco Mancuso, by marking the boundaries between inside and outside and naming the often-overlooked elements throughout the space—revealing its spatial origins and the stories embedded within. Like captions to the Pavilion itself, these annotations include everything from basic information such as the names of the architects and the date of completion, to the surrounding trees that inspired the Pavilion’s form, as well as descriptions of things that once existed but have since disappeared. This approach invites visitors to experience the original intentions of the architects, who – adhering to Venice city regulations emphasising com’era, dov’era (as it was) – raised a lightweight steel structure on a pilotis, seeking to blend seamlessly into the park without disturbing existing tree roots, and to create a demountable form. Particularly highlighted are spaces that had long gone unnoticed—such as the roof, the rear elevation of the building, and the underside of the pilotis, which the curatorial team refers to as the ‘underground’.

The metaphor of the ‘house’ in the Korean subtitle of the exhibition, ‘Time of House’, offers an intriguing shift in perspective: it challenges the entrenched notion that exhibition halls must remain expressionless white cubes and invite expansion into times and subjects beyond an exhibition. Pai Hyungmin (professor, University of Seoul), who has participated in the Venice Biennale in various roles, likewise interprets the Pavilion as a house. The bright exhibition hall one encounters upon entering, opening to the gardens and the waters of the San Marco Canal, is a ‘living room’, while the square brick shed that once used as an office and toilet hides like a ‘bedroom’. He questions whether the concept of the white cube ever truly existed in the short history of Western-style painting in Korea, and praises architect Kim Seok Chul for creating responsive architecture that maintains the scale of a house while adapting flexibly to exhibitions.▼1

A house inherently presumes life, and within the time of life, multiple actors and relationships inevitably become entangled with space. Novelist Kim Geumhee, in writing her fictional work The Big Greenhouse Repair Report (2024), reflected on how Changdeokgung Palace’s greenhouse is also someone’s ‘house’. She likened the greenhouse – whose significance has shifted from the Japanese colonial period to the present – to a ‘survivor’, wishing that all beings present in that period are rightfully remembered. Her words echoed far away, across the Korean Pavilion in Venice. Viewed through the lens of a house, the Pavilion is not an empty exhibition space active only during the Biennale, but a site that invokes the park life in Venice and the numerous overlooked presences woven through its history.

30 Million Years Under the Pavilion by Young Yena. Photo by Choi Yongjoon / ©Korean Pavilion 2025

Time for Trees by Park Heechan. Photo by Choi Yongjoon / ©Korean Pavilion 2025

Commissioned Works: Dismantling and Reconfiguring Boundaries

The second component of the exhibition comprises commissioned works by four artists. Through archival research and observation, they aimed to awaken and amplify the Pavilion’s presence. The curatorial team describes this feature of the commissions as architecture made of thread and light. It captures how the artists equip the Pavilion, which is sensitive to nature, to be perceived through flexible and ephemeral materials such as fabric, thread, and cables. By likening the thirty-year-old Pavilion to a house and caring for it through remembrance, and by showcasing artists’ subtle engagements with the space, the exhibition mirrors the real-world conditions of architects today; passing through an era of construction, facing the climate crisis, and needing to revisit and care for what we have built.

At the Pavilion’s entrance, visitors encounter a cat lying on a fabric plan of the Pavilion, like a cushion—Lee Dammy’s Overwriting, Overriding. As suggested by the Latin meaning behind her practice’s name Flora and Fauna, Lee focuses on speculative architectural imagery between plants, animals, objects, and buildings. She has built a private, alternative archive featuring the honey locust frequently seen in photos of the Korean Pavilion and the stray cat Mucca, which casually wanders between the pavilions. Imagining tree roots connecting in all directions, regardless of human-drawn boundaries, she represents architects not as makers of fixed structures with exact dimensions, but as facilitators of fresh relationships through soft, mutable materials.

The meeting of the brick room, the oldest part of the Pavilion, with Young Yena’s 30 Million Years Under the Pavilion is significant. She posits a fictional scenario where Nanogyna, a creature from tens of millions of years ago, is discovered under the pilotis of the building, transforming the Korean Pavilion into a virtual archaeological site. Overwhelming double bubbles fill the brick room like incubators to preserve Nanogyna fossils, and made-up records documenting its behavior and language line the walls. Noting the Pavilion’s suspended form as distinctive, she filmed real animals, such as hedgehogs and cats, reacting to the half-buried Nanogynas under the pilotis, streaming these intersections of virtual and real into the exhibition in real time. The bubbles are materials and a medium that Plastique Fantastique – led by Young Yena and Marco Canevacci – have long explored and developed. The bubbles without a roof, wall, or window lead us to the future by dismantling boundaries meaninglessly and playfully, and imaging network of relational space.▼2 In the Korean Pavilion, these bubbles, holding unknown lives, propel us beyond national boundaries to a primordial place.

If Lee Dammy and Young Yena work to dismantle the boundaries of architecture through non-human or imaginary agents, Park Heechan and Kim Hyunjong transcend those boundaries by physically reconfiguring the Korean Pavilion. Park Heechan’s Time for Trees is a series of architectural devices designed to sense the unique relationship forged with the Pavilion, which was conceived with equal consideration for both surrounding trees and the building itself. He recalls being deeply impressed during his visit to the Korean Pavilion’s 2024 art exhibition, where artworks could be viewed against the ever-changing natural backdrop through transparent glass walls. His sketches from that time show trees and architecture merging seamlessly, blurring their boundaries, and reminding us that both nature and the artificial are changing. To amplify that impression, he installed A Shadow Caster on the glass wall, a four-tiered screen that captures shifting tree shadows in response to changing light, and, in front of it, he placed Elevated Gaze 1995, a periscope-like structure that reflects rooftop views. At the centre of the gallery sits Giardini Travelers, a modular truss system that can be folded and repurposed as benches, ladders, tables, or stairs. Equipped with wheels, this mobile device serves as a kind of negotiator, enabling events to travel to various national pavilions throughout the Giardini.

Originally conceived as the fourth gallery of the Korean Pavilion, the roof terrace was designed to be open to Venetian citizens, as a place where one could encounter the drama of the sea and sky. Symbolising the Pavilion’s publicness, the terrace gradually faded from memory when the Giardini ultimately remained closed to the public, and the original spiral staircase within the cylindrical volume, deemed disruptive to exhibitions, was removed not long after completion. Kim Hyunjong has envisioned a new roof structure, New Voyage for this space, inspired by the grid motif evident in early design archives and the Korean Pavilion’s formal gesture of unfurling like a sail toward the sea. His intervention seeks to reimagine the rooftop as a space of welcome and a symbol of cultural exchange. Yet, the existing stairway, tucked discreetly along the building’s exterior, fails to naturally guide visitors upward. Without intentional effort, the terrace remains difficult to find, lingering as a symbol of the Pavilion’s unrealised vision.

This exhibition tells too many stories to expect coherence across the works. While all of the works are based on archives, the exhibition in the Korean Pavilion has numerous layers of extensive research and diverse interpretations of participating artists. The high density of the Korean Pavilion’s architecture exhibition has been noted in every iteration; discerning visitors will find their own reflections between these fragments, yet visitors moving briskly through the vast Biennale grounds require considerable prior knowledge to fully grasp the context and messages.

New Voyage by Kim Hyunjong. Photo by Choi Yongjoon / ©Korean Pavilion 2025

A Shadow Caster and Elevated Gaze 1995 by Park Heechan. Photo by Choi Yongjoon / ©Korean Pavilion 2025

Korean Pavilion, Giardini, and the Biennale’s Future: Beyond National Borders

The narrative that shapes the Pavilion’s meaning and future, as the curators wish to convey through history, concludes in the catalogue. One-third of the catalogue is devoted to a visual curatorial essay that decodes the archive of the Pavilion and Giardini. Through this essay, the curators reflect on the challenges faced by the Korean Pavilion – joined in the Giardini as the last national pavilion of the 20th century within a space built to display national identity – and on the optimism of publicness and solidarity dreamed jointly by Kim Seok Chul, Franco Mancuso, Korea, and Italy. These messages culminate in the radical proposal by Song Ryul and Christian Schweitzer to ‘relocate the Biennale entirely to the Arsenale grounds, with national exhibition areas distributed annually through random selection’—a call to rethink the possible obsolescence national pavilions at a time when global cooperation and equality are essential to survival. In the Venice Biennale, which has maintained its status as the world’s largest architecture biennale by drawing support on a national level through its national pavilions and awards system, ironically, Korean Pavilion’s architecture is seen to be a symbol of borderless solidarity, transcending the concept of nationhood.

Today, as more and more people grow weary, even oversaturated, by the increasing number of Biennales, the Venice Biennale itself is being called into question. Yet if we take a step back, we realise that over the past thirty years, we have never truly examined what we are doing or in what context we are doing it. Without an understanding of our past and present foundations, on what basis can we imagine the future? This exhibition, commemorating the 30th anniversary of the Korean Pavilion, finds significance in setting a new starting point for reflection, repositioning us all to reconsider the Biennale as a site of knowledge and discourse production.

1 Pai Hyungmin, ‘Dwelling on the Korean Pavilion’ in Common Pavilions: The National Pavilions in the Giardini of the Venice Biennale in Essays And Photographs, ed. Diener & Diener Architects with Gabriele Basilico, Zurich: Scheidegger & Spiess, 2013.

2 Lidia Gasperoni, ‘Space without Roots’ in Marco Canevacci, Yena Young, Plastique Fantastique: A Journey through an ephemeral realm, DCV, 2023.

CAC, curator of the Korean Pavilion and artists (from left) Jung Sungkyu, Lee Dammy, Kim Heejung, Young Yena, Chung Dahyoung, Kim Hyunjong and Park Heechan. Image courtesy of Arts Council Korea / ©Choi Jinbo

Photo by Choi Yongjoon / ©Korean Pavilion 2025