SPACE May 2025 (No. 690)

Now that a second Chinese architect has been awarded the prestigious Pritzker Prize, SPACE turns its attentions in this issue to Chinese architecture. It has not been addressed with the same critical depth as the well-documented architecture of Japan. Since the implementation of its Open Door Policy in 1978, China has experienced a dramatically transformed design environment, and the new generation of architects that emerged in this period led the new direction in architectural discourse from 1990 onwards. The focus of this FEATURE, Chang Yung Ho, is widely regarded as one of the most influential figures at the centre of this movement, shaping the trajectory of contemporary Chinese architecture.

Inha Jung (professor, Hanyang University), the interviewer of this FEATURE, is a scholar who interprets the history of modern architecture in East Asia as the convergence of an imported Western modernity and a regionally specific, indigenous modernity, suggesting that both forms have long coexisted. He views Chang Yung Ho’s work within the broader framework of modern architecture in East Asia. Throughout this interview, Jung examines Chang’s architecture both diachronically and thematically, revealing how modern Chinese architecture often reaches beyond its domestic scope to follow a bold new trajectory.

Wenzhou Medical University International Exchange Center (2023). Characterised by extremely deep eaves, the units are separated only by narrow gaps of 50cm. As a result, the Wenzhou Medical University International Exchange Center’s campus is composed of four-layered spatial arrangement from the center to the periphery: the central courtyard (outdoor), the indoor, the veranda (semi-indoor), and the area under the overhang (semi-outdoor). This emphasis on creating outdoor and semi-outdoor spaces is intended to encourage people to spend more time outside – shielded from sun and rain – taking advantage of Wenzhou’s mild climate, as implied by the city’s name, which means ‘warm prefecture’.

The Concept of Vision in the Chinese Garden

Inha Jung: In several books and articles that deal with your work and ideas, I discovered that you place strong emphasis on the concept of vision. In particular, you compare the experience of the Chinese garden with a space designed by Western linear perspective, and you’ve often described the differences between the Western linear perspective and the traditional Chinese way of seeing. I assume that your education in the U.S. played a role in developing this idea further. Could you introduce some of your projects that illustrate the contrast between Western perspective and Chinese traditional way of seeing?

Chang Yung Ho: The Chinese garden is deeply connected to traditional Chinese notions of time and space. As we all know, the Western idea of space is conveyed through a timeless perspective. It’s the scientific approach—analytical and precise. You separate time from space and to observe space on its own which essentially means suspend time and vice versa. But in China we never do that. Traditionally, time and space are always intertwined all the way through. That means time has to be designed in architecture. I understood that conceptually, but I didn’t know how to apply it. Let me give you an example, the No Name Art Museum (2021). In this project I used perspective, which for me is a very familiar tool. I learned it from rofessor Sun during my time at Nanjing, and when I came home, my father even tested me on perspectival drawing. So I understand the Western perspective thoroughly, but in this project, I use it to construct more dynamic, changing experiences of time and space. It was not about expressing something Chinese or Asian, but about mixing both ideas to realise the design of time to some extent. In the No Name Art Museum, as you move through, your perspective changes. The space would feel more compressed or stretched depending on your point of view.

Inha Jung: In your book Zuo Wen Ben (作文本, 2005; revised 2023), you mention Alfred Hitchcock’s film Rear Window (1954) several times. I also heard that you mention this in a design studio in the University of Michigan and Berkely. In this discussion, you emphasised the meaning of windows on the façade, but also talked about the role of furniture in space. It made me wonder—was your main focus on the façade or on a matter of space?

Chang Yung Ho: It was definitely about space. However, I understand your confusion, since I started to mention the window. The idea was how to make a window spatial, so that the window becomes a room, and eventually a space by itself. My window-furniture drawings were published in the UC Berkeley University’s student magazine Concrete and I later realised this drawing in real furniture in Shenzhen. They were inspired directly by Rear Window. Ultimately, it was more about how to read windows as a way of figuring out spaces and to decipher spaces from within.

Material Experimentation

Inha Jung: I know that you organised the exhibition ‘Material-ism’ (2012) at UCCA. There you expressed the importance of material experimentation. What was your motivation for planning this exhibition?

Chang Yung Ho: For me it’s all about trying to understand architecture as a way of taking on the tangible world. At the time, architectural discourse seemed overly focused on ideas – conceptual, abstract ideas – and I felt that wasn’t the right direction for us. So, within our office, we decided to take a different approach: to move from material to idea, rather than from idea to material. From hand to head, not the other way around. Starting in 2012, we began selecting the material for each project at the very beginning. And once we had the material, we explored its structure, construction method, and spatial implications—though of course, in reality, all of those things happen almost simultaneously.

Inha Jung: What kind of change did you experience after the exhibition?

Chang Yung Ho: The biggest change was the improvement in the overall quality of our work—not just in terms of materials, but in terms of the spatial experience as well. One example is the Wenzhou Medical University International Exchange Center (2023), where we created huge canopies that almost touch each other. We studied both the climate and available technology in depth and the lifestyle. To me, architecture is always a response, both to climate and to the way people live. And what’s interesting more recently is that we’ve become increasingly involved not only in the design of buildings but also in programming them. We now often propose to our clients how a building might be used. Sometimes, even at the urban scale, we suggest that they include public or commercial components that weren’t in the original brief, both large and small. After running my office for so three decades, I don’t know if we can always maintain that level of quality. But from time to time, we manage to create very good concrete structures. There’s Nanjing Normal University Affiliated High School, which will be open in September 2025, and the quality of concrete there is really fantastic. However, we then ask the question: does the quality of the concrete surface truly represent the quality of architecture? Or is it simply a reflection of superior construction technology? We’re still trying to achieve that kind of smooth and shiny finish. That said, we’ve also come to realise that in a world where virtual reality exists, physical reality has to offer something else, something tangible. When you touch it, it should probably feel rough. You should be able to sense its temperature. And, of course, it should show subtle changes with the seasons and the weather. So now, we’ve also learned how to make rough buildings; not refined buildings, but rough buildings. One of the projects where I think we did a pretty good job is the Nantou Neighborhood Center (2023) in Shenzhen. We often refer to it as ‘a huge pile of brick’.

Inha Jung: I’ve noticed that you use a lot of new materials, such as plastic, fibreglass, and glass concrete. Do you plan to continue working with these materials?

Chang Yung Ho: That’s actually a tricky issue. Many new materials can’t be used in large-scale structures because of government regulations. So in most cases, we have to rely on more conventional materials. In small, experimental buildings, it’s still possible to use new materials. We continue to experiment, but it’s not easy to offer these options to clients in typical projects.

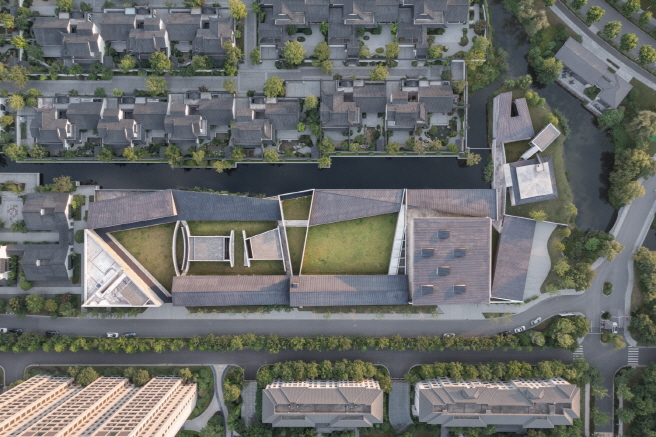

China Academy of Art (CAA). Liangzhu Campus Phase 1 (2023) The new Liangzhu Campus of CAA, one of leading art universities in China, is an experimental project aimed at shaping a future educational model for an arts-based comprehensive university. The campus envisions an ‘open campus’ and spatially embodies new educational principles: foundational education that engages both the head and the hand, curricula where classes themselves function as research, and the dismantling of departmental boundaries. Instead of traditional classrooms, open studios where all activities are visible and vaulted spaces filled with natural light encourage students to actively occupy, experiment with, and shape the campus culture. Dormitories are placed above the studios, creating a vertical configuration that realises the idea that ‘living is learning.’

The Domestic Prototypes

Inha Jung: Of your many built projects, I’m especially interested in the Vertical Glass House (2013). When you explained the intention of design, you referred to Mies van der Rohe and Philip Johnson’s glass houses. But to me, it also recalls traditional Chinese architecture like the folklore house in Jiangnan area or Shanghai lilong houses. I see this project as an experimenting the domesticity of Chinese architecture. What are your thoughts on this?

Chang Yung Ho: I don’t think it’s about Chinese vernacular houses, or whether they were used as my reference for the Vertical Glass House. It was more an exploration of what an urban glass house could be. I didn’t mention the name, but I was also thinking about John Hejduk. And of course, there’s Le Corbusier, who described the house as a machine for living. I’ve always been interested in ideas related to the glass house. At the same time, I was thinking about how to design for a city with a certain level of density. That’s why there are no windows on the walls but only on the roof. The roof is a skylight that becomes the primary opening. So this is, in a way, more about a glass house for the city.

Inha Jung: Many Korean and Japanese architects have also studied a similar case— inward-facing houses, where the openings are oriented not toward the outside but inward. The Vertical Glass House seems to share this characteristic. I think it is like one of prototypes which shows the inward-looking tradition in East Asia.

Chang Yung Ho: That’s correct, it’s definitely an introverted house. we’ve designed quite a few projects that derive from the courtyard-house prototype. Some of them are much closer to traditional forms, while others are attempts to develop a more modern, more contemporary version if I can find it. But the core idea remains the same: a house ought to be introverted, only opens up to the sky and the earth in the middle.

Inha Jung: You also designed Studio Houses (2022) in Ningbo. Each of the four houses seems to have its own take on the courtyard prototype. Could you explain the design intentions behind each one?

Chang Yung Ho: Three of the four houses were actually designed in the early 1990s – mostly around 1991 – when I was still a paper architect without clients or sites. At the time, I was trying to rethink the traditional courtyard house, with rooms arranged around a central void. The fourth house is different. There, I focused on the role of the roof. The roof became the central organising element that divides the space into two parts—one for working and one for living. They coexist, but also function as two distinct components. Right now, I’m also designing a new house in Houston, Texas. It’s small, but it’s another prototype that explores what a single-family house can be today, architecturally. East

Nantou Neighborhood Center (2023). It is a multifunctional complex built on the site of a former community service facility, renovated to accommodate a hospital, community offices, exhibition spaces, and classrooms. Referencing the architectural scale of Urban Villages (cheongzhongcun), the building is divided into four volumes, each morphologically differentiated according to its specific function. Open corridors and exterior staircases weave these volumes into a three-dimensional alleyway network. The faÇade combines grey and red bricks in varying proportions, giving each volume a distinct identity while achieving overall harmony.

Asianness in Architecture

Inha Jung: The final topic I’d like to ask about is the East Asianness in architecture. You organised The Commune by the Great Wall in 2002, which was the first attempt to collaborate with Asian architects. What was your motivation in selecting architects from Asia?

Chang Yung Ho: At the time, my thoughts weren’t as clearly articulated as they might be now, but I simply wanted to explore the sensibilities of Asian architects. Fortunately, the client, Zhang Xin, appreciated the idea. And that’s how the collaboration with architects from across Asia came about.

Inha Jung: You also served as a juror for the international design competition for the Asia Culture Center in Gwangju, Korea. The Korean architect Kyu Sung Woo’s proposal was selected as the winning entry. What did you think of his project, and what was your concept of Asianness at the time?

Chang Yung Ho: Of course, the jury process was anonymous, so I didn’t know who the architect was at the time. Most of the entries – whether by Western architects or Asian ones – were about designing objects. Some were quite interesting. I remember the proposal by Coop Himmelblau being visually exciting. But ultimately, they were all just objects. There was only one project that addressed negative space – a void – and it did so very clearly. And I thought, that is an Asian idea. It comes down to a fundamental difference in how space is created. In the West, when you’re given a piece of land, the tendency is to place objects on it, and space is something that emerges around them. In Asia, by contrast, you enclose space, that is you create a space in the middle by defining its boundaries. That one project stood out for embracing the void. It turned out to be by a Korean architect. I didn’t know him then, but the jury asked me to contact him, and I later met him at MIT.

Inha Jung: Based on those two experiences and your broader reflections, how would you define East Asian architecture? What are its key characteristics?

Chang Yung Ho: It’s hard to define in just a few words. But in a general sense, what I do believe is that while we as human beings might share a broad understanding of architecture, every place expresses that understanding differently through its own culture and history.

ChunYangTai Arts and Cultural Centre (2023). It is a cultural facility surrounded by lotus ponds near Langtou, a 600-year-old ancient village on the outskirts of Guangzhou. Referencing the village’s scale and spatial structure, the programmes – including exhibition halls, a theatre, a library, research studios, and a café – is distributed across ten small buildings. These volumes are connected by ‘towers’ featuring curvilinear brick walls, forming alleys and courtyards between them. About 30 ponds are installed on the rooftops, creating a natural landscape while improving energy efficiency, and together with the sunken courtyards and surrounding water features, they form a multi-layered aquatic system. Traditional architectural elements such as the dragon boat ridge and crescent-shaped moon windows are reinterpreted in a contemporary manner using regional materials like red tiles, grey bricks, and exposed concrete.