SPACE May 2025 (No. 690)

Now that a second Chinese architect has been awarded the prestigious Pritzker Prize, SPACE turns its attentions in this issue to Chinese architecture. It has not been addressed with the same critical depth as the well-documented architecture of Japan. Since the implementation of its Open Door Policy in 1978, China has experienced a dramatically transformed design environment, and the new generation of architects that emerged in this period led the new direction in architectural discourse from 1990 onwards. The focus of this FEATURE, Chang Yung Ho, is widely regarded as one of the most influential figures at the centre of this movement, shaping the trajectory of contemporary Chinese architecture.

Inha Jung (professor, Hanyang University), the interviewer of this FEATURE, is a scholar who interprets the history of modern architecture in East Asia as the convergence of an imported Western modernity and a regionally specific, indigenous modernity, suggesting that both forms have long coexisted. He views Chang Yung Ho’s work within the broader framework of modern architecture in East Asia. Throughout this interview, Jung examines Chang’s architecture both diachronically and thematically, revealing how modern Chinese architecture often reaches beyond its domestic scope to follow a bold new trajectory.

Split House (2002). A residential building designed by Chang Yung Ho as part of the Commune by the Great Wall (2002), which involved collaborations with various architects from across Asia. The house is split right in the middle, to save trees already on the site, separating public functions from private ones, and bring the natural scenery into the embrace of the residence. It is also attempt to transplant siheyuan, a traditional courtyard house adapted to the dense urban context of Beijing, into the prisine landscape, to create a flexible prototyepe of houses located in the valley, and to make a building that can be easily disintegratable.

Modernity and Chinese Architecture

Inha Jung: Let me begin with a question on modernity and Chinese architecture. I believe there are two kinds of modernity in East Asian architecture—one imported from the West, and another that reflects the East Asian way of life. I suppose these two kinds of modernity coexisted for quite some time in the history of East Asian architecture, but eventually with the passage of time, conversed into a single trajectory. I think the timing of the shift, however, varied by country—occurring in Japan in the early 1970s, in Korea in the late 1980s, and in China, the late 1990s. I believe this framework is essential when explaining the narrative of modern architecture in East Asia. I would like to ask for your opinion on this critical point.

Chang Yung Ho: Rather than discussing it in terms of a time frame, I’d like to offer a simplified explanation of how architecture – as a field and profession – was introduced to China. Of course, people in every culture have always built things. But what we’re discussing here is a very specific conception of architecture, one that originated in the West. The idea of the architect as a clearly defined profession probably began during the Renaissance in Italy. From that point, architecture developed into a discipline with a specific body of knowledge associated with it. When this idea entered China – mainly through students who had studied at the University of Pennsylvania in the U.S. – it wasn’t received as an anthological body of knowledge, but more as a notion of style. These students studied classical architecture. They chose Philadelphia over Paris because architectural education in Paris had begun to shift, focusing more on architecture as a form of social practice. As a result, some professors left Paris in search of work elsewhere. The Chinese students who went to Philadelphia studied architecture under the umbrella of classicism, but were also exposed to other formal vocabularies, even ideological ones to some extent. When they returned to China, most of them designed a solid sort of classical design as their output, though some also experimented with modern buildings. But for them, it was just a formal or stylistic exercise. That was in the early 1920s. For architects like Yang Tingbao▼1, these exercises were very important. In fact, it’s unfortunate that some of his best modern works were probably even better than his classical ones. So, within that context, I don’t think students in the 1920s were ignorant of modernism, but I also don’t think they were really concerned with the idea of modernity. They didn’t think deeply about what modern meant—they just acquired the design skills. These architects then taught the second generation of Chinese architects, who were usually educated within China. My father▼2 was one of this second generation of Chinese architects. He wasn’t much of a modern architect, but he had a strong interest in Art Deco. One interesting point, I think was that that generation was stylistically open-minded. Although I’m not a historian and may not have all the facts, unlike Japan, China didn’t have any architects who worked in Le Corbusier’s office. Japan had at least two or three. Another point I’d like to mention is that in Postmodern Singapore, one of William S. W. Lim▼3’s books, he argued that in Singapore, modernism and postmodernism emerged at the same time. That seemed important to me when trying to understand how any kind of sequential relationship between the classical and the modern can be thought to have taken place in Asia. In China, this was probably less complex because it’s still fairly early. In Singapore, I would say, probably also in 1980s – it’s not really much later than China, but it didn’t start as early as China – classicism, modernism and postmodernism flourishing all at the same time. William S. W. Lim was also himself a practitioner, known as the designer of the People’s Park Complex (1972) and Golden Mile Complex (1974).

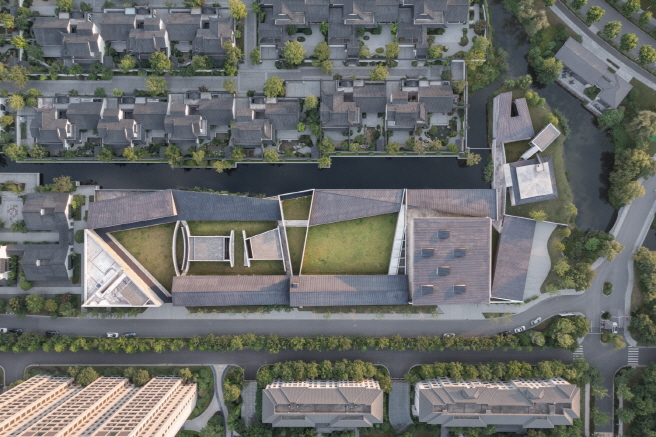

The Bay (2010) The project’s site of nearly 45 hectares, located in Qingqu district, Shanghai, was once used as a fishpond, with an ecological environment. Following that, the house was developed with a set of keywords— disperse, courtyard, and garden. Also, there is intend to reinterpretation of the rigional heritage by using the form of the gable wall and slped roof, which reflect the traditional building elements in the vernacular architecture of the south, together with the untraditional construction materials like grey stone, aluminum alloy doors, windows and roofing, a steel channel that frames the wall. ©Shu He

Education in Nanjing and U.S.

Inha Jung: Returning to your personal experiences, I would like to ask about your education in China. You were born and raised in Beijing, but eventually chose the Nanjing Institute of Technology. Was there a particular motivation to move to Nanjing to study architecture? Did the fact that your father, Zhang Kaiji, was an alumnus of the same school influence your decision?

Chang Yung Ho: The answer is yes. During the Cultural Revolution, from 1966 to 1976, universities and colleges were closed for ten years. I applied for university in 1977, which was the first year after the Cultural Revolution that national entrance exams were held. At first, I thought about applying to art school to study oil painting. I still enjoy painting and drawing, but I was really bad at it. My relatives and friends all said, ‘Don’t apply to art school. You won’t get in.’ And they were right. That’s when my father intervened, saying ‘Maybe, you ought to consider architecture. You don’t need to draw particularly well.’ My mathematics was terrible too, but he said that wouldn’t be a big problem in architecture either. That year, I could apply to only two schools: Tianjin University and the Nanjing Institute of Technology, due to the trauma from that period, many universities were still unable to open. I ended up getting into Nanjing.

Inha Jung: Could you briefly introduce the curriculum at the Nanjing Institute of Technology at that time? What was the atmosphere like in the studios?

Chang Yung Ho: At that time, architecture was taught in a Beaux-Arts style—the traditional, classical approach. We learned drafting and rendering at the same time from the very beginning. For rendering, we used either watercolours or Chinese ink. But the professors didn’t allow us to discuss formal or aesthetic ideas. We acquired classical techniques, but we never really explored classicism as an aesthetic sort of a system. In studio class, we started design from small-scale buildings and gradually expanded. In the first year, we designed a small post office. Then the projects grew larger—schools, office buildings, theatres, and so on. It wasn’t really education for the mind; it was more about kind of training for the hands. Still, students like me were so happy to be able to have a higher education. We were so eager that we used to sneak into the library, which was off-limits to undergraduates, just to look up the works of Mies van der Rohe and other architects. Their work felt fresh, new, and young to us.

Inha Jung: While studying in the Nanjing Institute of Technology, did you have any mentor who had a lasting influence on your development?

Chang Yung Ho: When it comes to mentors, I’d mention professor Sun Chongyang▼4, who taught my first-year studio. He was a very rigorous instructor. There’s one story that really stuck with me and helped to give you a sense of what I learned from him. It was during the first-year post office project. When I was doing the rendering, I didn’t want to draw every single piece of brick— I thought it would make the drawing look too rigid. But I didn’t know where to stop, so in the end, I drew every brick anyway. When professor Sun came by, I told him, ‘This isn’t what I really wanted to draw—I wanted to express it differently.’ And he said, ‘You did the right thing. This is architecture.’ I didn’t quite understand what he meant at the time. But looking back, I realise he was right. I think even then, he was already thinking about architecture in a very ontological way.

Inha Jung: Next, I’d like to ask about your studies in the U.S. You first attended Ball State University. Was there any particular reason for choosing that school?

Chang Yung Ho: I started studying in Nanjing in 1978, which was around the time when China and the U.S. were beginning to reestablish diplomatic relations. There was an architecture professor at Ball State University who was interested in visiting China. His name was Marvin Rosenman. Although he knew that diplomatic relations had gathered new momentum, he didn’t really know how to get a visa or arrange a visit. One day, he happened to be reading House & Garden, a magazine mostly for housewives, and he came across an interview with a Chinese architect who turned out to be my father. He contacted the magazine and asked for my father’s contact information. Then my father introduced him to the Chinese Society of Architecture, and professor Rosenman was eventually able to bring a group of 19 students from Ball State University to visit four Chinese cities with major architecture schools in China. Since I was studying in Nanjing at the time, I met professor Rosenman there. Later, my father asked him if he could take me to the U.S.—not as part of the student group’s trip, but perhaps afterwards. And that’s how it all began.

Vertical Glass House (2013). The concept of this house was originally awarded the Honorable Mention in the 1991 Shinkenchiku Residential Design Competition, later constructed in 2013 as a permanent pavilion for the West Bund Biennale of Architecture and Contemporary Art in Shanghai. This is a prototype for high-density contemporary urban living, and also as a house with the notion of transparency in verticality, critisising the modernist transparency in horizontality, present a new interpretation of the modern theory of ‘architecuture as living machine’. ©Lyu Hengzhong

_

1 Yang Tingbao (1901 – 1982) was one of the first-generation modern architects in China and is considered one of the ‘five masters of Chinese architecture’, alongside Liu Dunzhen (1897 – 1968), Lü Yanzhi (1894 – 1929), Liang Sicheng (1901 – 1972), Tong Jun (1900 – 1983). [Refer The Five Masters of Architecture (建筑五宗师, 2005) by Yang Yongsheng (1931 – 2011), a prominent figure in China’s architectural publishing industry.] Alongside Liu Dunzhen and Tong Jun, he was also among the first generation of professors to establish architectural education at Southeast University. He studied architecture at Tsinghua College and the University of Pennsylvania. Upon returning to China, he co-founded Kwan, Chu and Yang Architects and worked on major projects such as the Liaoning Central Station and the master plan, library, chemistry building, and dormitories of Northeastern University.

2 Zhang Kaiji (1912 – 2006), the father of Chang Yung Ho, was an architect born in Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province. He studied architecture at the Nanjing Institute of Technology and later became chief architect at the Beijing Institute of Architectural Design. He is widely regarded as a representative architect of the Maoist era.

3 William S. W. Lim (1932 – 2023) was a Singaporean architect born in Hong Kong. He founded William Lim Associates (1992 – 2002) and later, the Asian Urban Lab (2003). His practice and writings focused on architecture, urbanism, cultural studies, and sociopolitical postmodernity in Asia. He authored 13 books—including Asian New Urbanism (1998), Alternative (Post)modernity (2003), Contesting Singapore’s Urban Future (2006), and Asian Alterity: With Special Reference to Architecture and Urbanism Through the Lens of Cultural Studies (2008)—and edited two additional volumes.

4 Sun Chongyang was a professor at Southeast University and is considered part of the third generation of architectural educators there. Along with colleagues Zheng Xunzheng and Wang Wenqing, he co-founded the so-called ‘Zheng-Yang-Qing Group (正阳卿小组)’, which had a significant influence on architectural pedagogy. Their aim was to integrate industry, academia, and research, and they co-authored publications such as Architectural Drafting Systems (建筑制度).

5 From the 1950s to the 1970s, under the Chinese Communist regime, all architectural practice was controlled by state bureaucracy. Architects were affiliated with state-owned architectural and urban design institutes under central or local governments, or with universities. In 1978, the Chinese government began implementing its Open Door Policy and made efforts to improve the design market. In 1995, it officially introduced the licensed architect system (注册建筑师, zhucejianzhushi) and established a certification examination.