SPACE April 2025 (No. 689)

Rapid population decline is shaking the fabric of small and medium-sized cities to the core. To rebuild these cities, we need to move away from the inertia of regeneration and take a perspective that acknowledging change. This is where the Mid-Size City Forum comes in. They look at phenomena outside the metropolitan area and seek urban and architectural alternatives to the crisis.

[Series] The Possibilities Inherent in Extinction, Mid-Size City Forum

01 What is Happening Outside the Metropolitan Area

02 Thinning Phenomenon

03 Urban Perforation

04 Erasing Plan

05 Ad-Hoc Architecture 1

06 Ad-Hoc Architecture 2

07 Global Mid-Size City

08 Temporary Mid-Size City

09 Resilient Mid-Size City

10 Fantastic Mid-Size City

11 Outside the Mid-Size City

View of 2025 Hwacheon Sancheoneo Ice Festival, Image courtesy of Hwacheon-gun

In recent years, the defining characteristic of small and medium sized (hereinafter mid-size) cities can be summed up in one word: ‘temporality’. To be more precise, it refers to a stark contrast between peak and off-peak seasons. Widespread mobility across the country and the numerous local festivals fiercely promoted by municipalities have only exacerbated this phenomenon. The influx of people, often outnumbering a local population several times over, arriving in a single day only to vanish in the next like a mirage, has become a new norm for mid-size cities. However, as we all know, certain disparities generate their own force. This is precisely why the Mid-Size City Forum seeks to uncover alternative possibilities in the face of these rapid cycles of change.

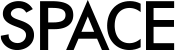

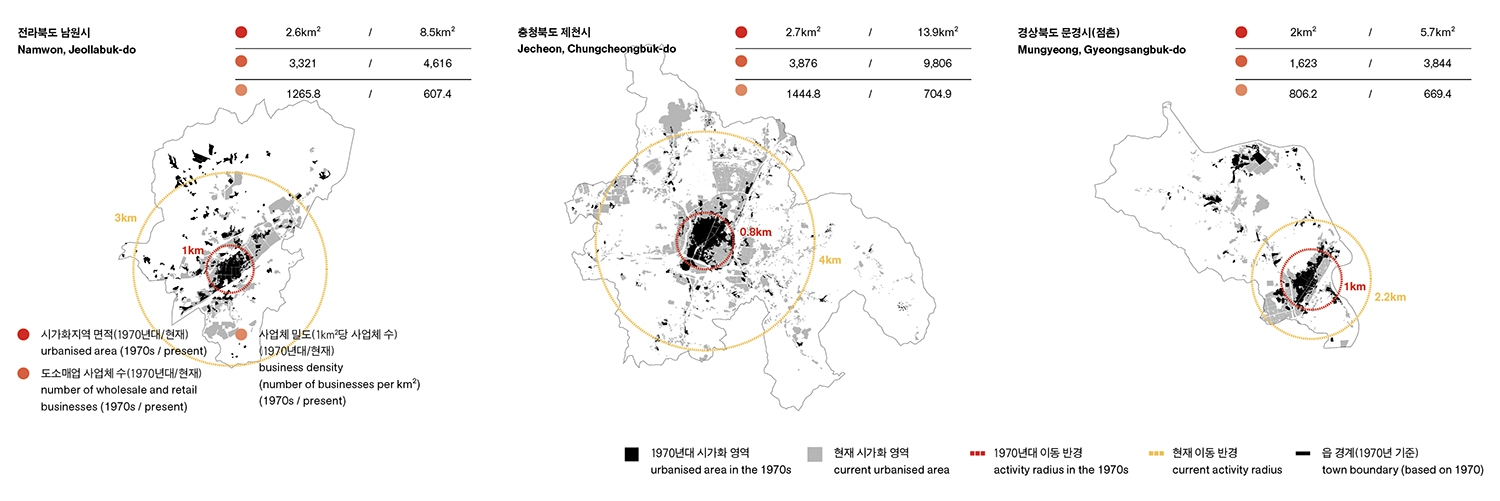

Diagram of programme dispersion and increased travel range in mid-size cities (1970s / present, data source: Statistics Korea). Since the 1990s, new housing developments on the outskirts of mid-size cities have been actively pursued across the country. As a result, urban areas have expanded rapidly while density has decreased.

Since the 1990s, most mid-size cities have experienced rapid spatial expansion, with their urban areas increasing significantly. However, despite this physical growth, the populations did not rise proportionally; instead, they began to decline. As a result, population density has thinned, and mid-size cities have been confronted with a new functional reality. The shift towards a new spatial structure has increased the reliance of urban citizens on cars, leading to fundamental changes in everyday life. On the streets, the presence of pedestrians has gradually diminished, while the number of cars on the roads has steadily increased. Coupled with these internal urban changes, a significant paradigm shift on a national scale also occurred from the 1990s onwards. The expansion of the motorway network across the country, combined with the sharp rise in car ownership, dramatically improved accessibility to regional mid-size cities. Furthermore, the introduction of the five workdays per week after the 2000s greatly expanded leisure time, providing a societal foundation for the growth of the tourism industry. These changes have prompted many mid-size cities to redefine tourism as a central strategy for urban survival. What new potential can be found in mid-size cities in light of these transformations?

Diagram of programme dispersion and increased travel range in Namwon, Jeollabuk-do (1980s / present). Residents now have access to a wider range of urban facilities, but the distance they must travel on a daily basis to use these services has significantly increased compared to the past.

Increase in Mobility

Up to the 1980s, the urban areas of most mid-size cities occupied less than half of their current land area. At that time, however, the population of these cities exceeded double the current number, and a dense, compressed structure had formed, with many citizens living within small, confined space. Since the 1990s, new housing developments on the outskirts of mid-size cities have been actively pursued across the country. This led to rapid expansion of urban areas, which in turn reduced population density overall. From 2010 onwards, the absolute population numbers began to decline, and the low density phenomenon in mid-size cities became widespread.▼1 This change also transformed the lifestyle of urban residents. In the past, a visit to the old city centre market would suffice to meet all daily needs. However, large supermarkets and various discount stores in newly developed residential areas now offer more affordable and higher-quality consumer goods. New cultural and consumption facilities for younger generations have emerged in these newly developed areas. In contrast, entertainment facilities previously located in the old city centre have also been relocated to these areas. Some government offices have also moved to these newly developed regions, leading to a decentralisation of related employment opportunities. As a result, residents of mid-size cities now have access to a wider range of urban facilities, but the distance they must travel on a daily basis to use these services has significantly increased compared to the past.

Declining population and increasing registered vehicles in mid-size cities (data source: Statistics Korea)

Despite the increased mobility within cities, mid-size cities continue to face the weakening of their public transportation systems. As various facilities have been dispersed across newly developed residential areas and the population has decreased, the number of public transport users has dropped. At the same time, the length of the routes has increased, placing transport companies under financial strain. As a result, the extended intervals between services has created a vicious cycle, further exacerbating a reduction in passenger numbers.

Meanwhile, large-scale apartment complexes have been built in the newly developed residential areas, providing more than one parking space per household and laying the foundation for expanding car ownership within the city. Unlike those in the old city centre, the supermarkets and commercial facilities established in these areas offer ample parking space, creating a car-friendly environment. A noticeable trend emerged in this period and has continued: the number of cars owned per person in mid-size cities has steadily increased. From the 2010s onwards, drive-thru (DT) establishments, representing a car-centric consumer culture, began to emerge in newly developed residential areas, further strengthening the car-dependent urban structure.

However, not all facilities typically found in a city centre have relocated or dispersed to the new residential areas, meaning that residents of mid-size cities now consider the two areas a single, integrated living space and constantly move between them. Unlike in the past, when various facilities were concentrated within a limited area and their usage hours were organically connected, allowing the city to remain in a state of continuous activity, the spread-out facilities have fundamentally changed how a city operates. As facilities, once concentrated in one place, have become spatially separated, their usage times have become fragmented, and the need to travel between them has increased. These separated facilities only become active at specific times. Once that time passes, they return to a dormant state, creating gaps in activity that appear and vanish intermittently throughout the urban space. Consequently, while ‘urbanity’, defined by continuous activity, has weakened, ‘mobility’, necessary to access the dispersed facilities, has become increasingly significant.

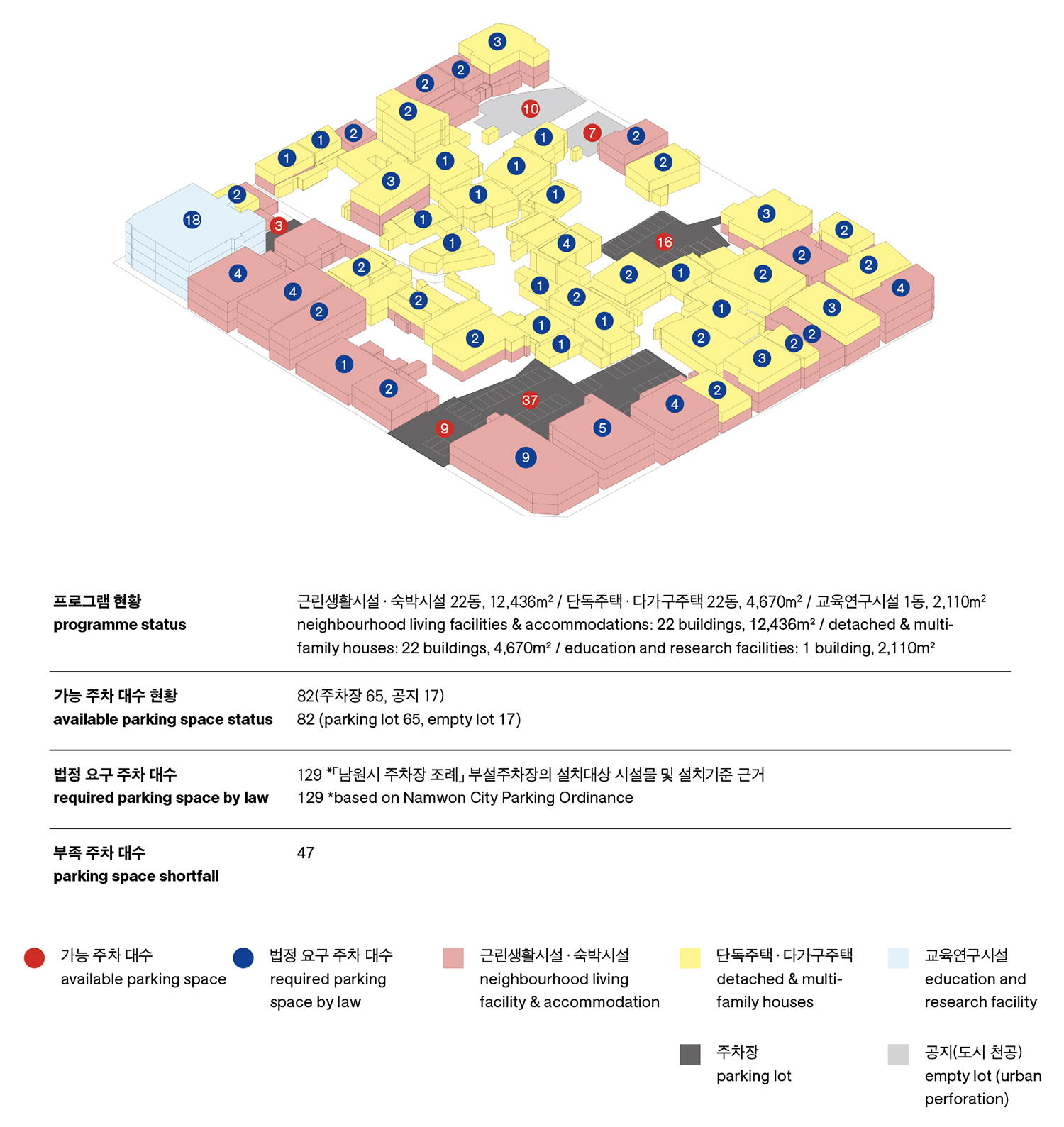

Analysis of the required parking capacity for a thick block in Namwon, Jeollabuk-do

Urban Structure and Parking Issues

Statistics reveal that while the populations of mid-size cities have consistently declined over the past 30 years, the number of registered cars within these cities has increased. Until the 1990s, the ratio of registered cars to the resident population in cities such as Jecheon, Namwon, Sangju, and Miryang was only 0.18, 0.14, 0.15, and 0.17, respectively. However, by 2024, these figures had increased nearly fourfold, reaching 0.58, 0.6, 0.64, and 0.63. Despite this rise in car ownership, the proportion of parking spaces in urban areas has not expanded accordingly. For example, in Namwon, the ratio of parking spaces to registered cars stands at only 69.7%. Similar figures are observed in other cities, such as Yeongcheon, Sangju, Mungyeong, and Jeongeup, where the parking capacity is notably low at 58.1%, 58.8%, 53.5%, and 65.5%, respectively.

The low proportion of parking spaces in mid-size cities stems from two structural factors. First, a significant number of buildings within these cities were constructed before the enactment of the Parking Lot Act in 1979, or, in the case of buildings built afterwards, they were approved before the stricter parking spatial requirements were enforced. Second, a considerable portion of the old city centre comprises ‘thick blocks’ (covered in SPACE No. 680). The plots within these thick blocks do not face roads accessible to vehicles, making it structurally impossible to provide parking for individual buildings. Consequently, roads outside the block boundaries are prone to parking congestion. For instance, within a single block in Namwon are 22 detached houses and multi-family houses, along with 22 neighbourhood living facilities and accommodation facilities. According to the current Parking Lot Act standards, 129 parking spaces would be required for this block. However, only 82 spaces are available. This figure has increased due to the perforation phenomenon inside the block due to population decline, which has led to the use of these areas as parking spaces. Without considering this, only 65 parking spaces would be available within the block.

In mid-size cities, where the parking capacity is structurally limited, the increase in the number of registered vehicles inevitably leads to the encroachment of parked cars onto road space. The vehicles occupying the roads range from long-term parking by residents of the inner blocks to cars temporarily parked during lunchtime to those briefly stopping at roadside businesses. With their varied time slots, these vehicles combine to create significant parking congestion on the roads. Local governments have been experimenting with various flexible approaches to alleviate this congestion and make the most efficient use of existing parking spaces. These include measures such as charging for on-street parking or creating variable-lane on-street parking areas, where parking spaces are first secured, and lanes are periodically shifted to prevent long-term parking. Nevertheless, mid-size cities have started to experience seasonal events that exceed the threshold of existing parking demand. These cities have entered a new phase in which the growth of the tourism industry is pushing flexible management approaches beyond their limits.

Views of an empty public parking lot on a weekday (left, Namwon Chunhyanggol Public Market) and peak-time traffic congestion on a weekend (right, Miryang Yeongnamnu Pavilion area)

Mid-Size Cities and the Tourism Industry

As the national territory has been restructured with a focus on the capital region, mid-size cities located geographically further away from this centre have increasingly relied on tourism. More than half of Korea’s population is concentrated in the capital region, where high-value industries are situated. This region continuously attracts related industries and young talent. In contrast, areas outside the capital region face serious issues, such as the decline of traditional manufacturing, significant ageing, and population decline, which has resulted in a steady reduction of the demographic groups capable of leading active consumer activities in the region. The weakening of consumer spending power has had a widespread impact on the local economy. It is particularly significant for mid-size cities, where the service sector plays a significant role in the economy. An analysis of the economic structure of these cities shows that a considerable portion of businesses in urban areas with active economic activity are concentrated in service industries such as wholesale and retail, accommodation and food services, and health and social welfare. According to statistics from the Statistics Korea, 81.7% of Namwon’s entire industry is related to the service sector. In comparison, other mid-size cities such as Jeongeup (79.4%), Gongju (81.3%), Jecheon (84.7%), Yeongcheon (73.7%), and Yeongju (83.6%) also show overwhelmingly high proportions of the service sector. The regional economy of mid-size cities, predominantly structured around the service industry, is inevitably limited in its ability to thrive with only residents whose purchasing power continues to decline. Therefore, strategies to actively attract consumers from outside the region are essential, which is why many mid-size cities have turned to tourism as a means of revitalising the local economy.

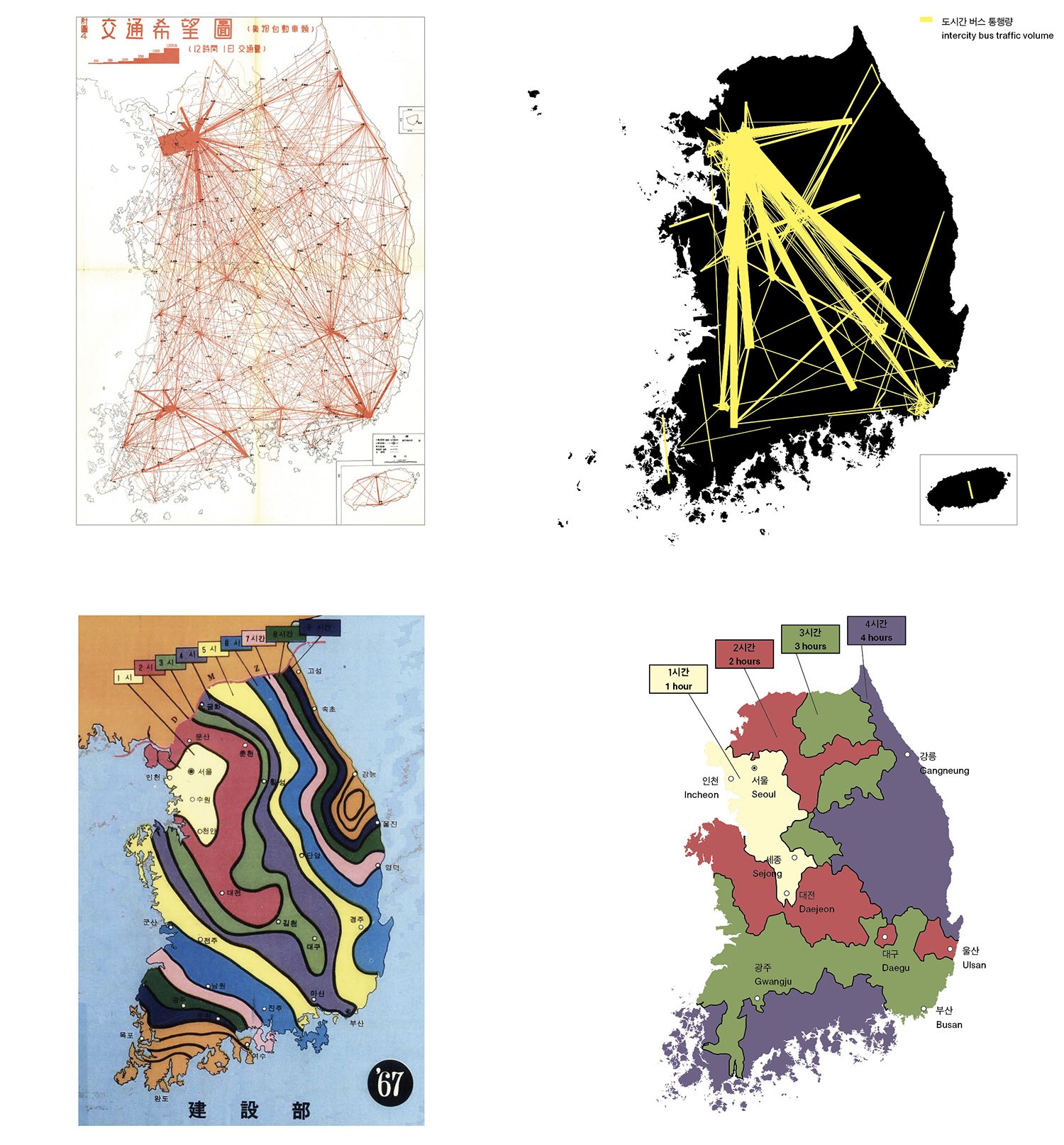

Since the implementation of the five workdays per week in 2003, urban dwellers have seen an increase in their leisure time, which has significantly contributed to the expansion of the leisure industry. The population concentrated in large cities and the capital region began to travel beyond urban areas on weekends to enjoy leisure activities, and the rapid expansion of the motorway network since the 1990s made many mid-size cities much more accessible. As a result, the convenience when travelling between the capital region and mid-size cities has dramatically improved. With the opening of new motorways, distances that once took more than eight hours to cover are now reduced to under three hours. According to the 1967 Comprehensive National Territorial Development Plan, it was expected that travelling from Seoul to Gangneung or Mokpo would take nine hours, to Nonsan, Yeongju, or Danyang would take six hours, and to Jecheon or Gongju would take five hours. However, all these areas can now be reached from Seoul in under three or four hours. With this compression of time and space, the connectivity between mid-size cities and large urban areas has been strengthened, increasing mid-size cities’ dependence on tourists from the capital region.

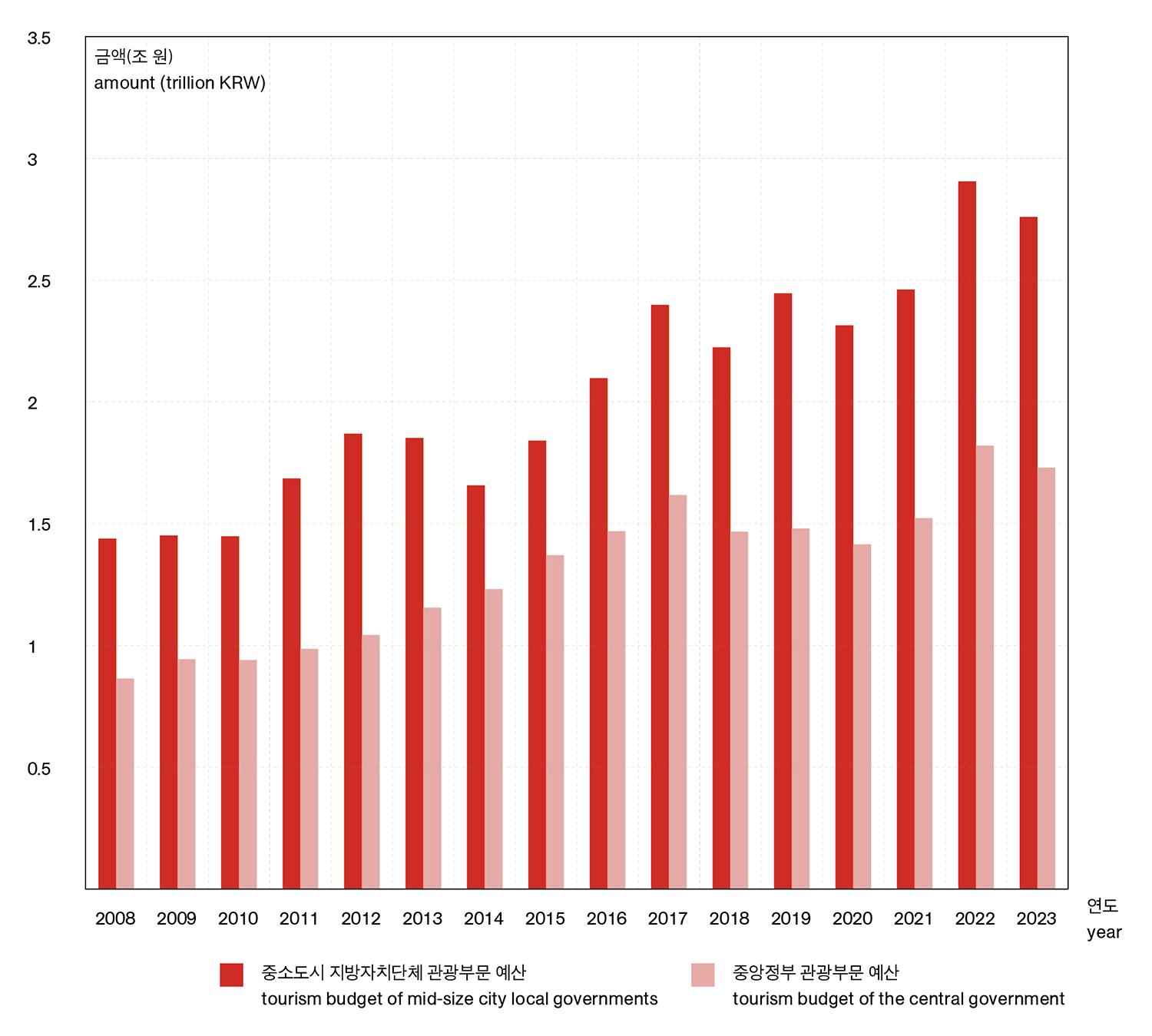

With the expansion of leisure time and improved accessibility, a foundation for the influx of tourists has been established, prompting local governments to invest competitively in the development of the tourism industry to revitalise the local economy through consumer spending by tourists. Over the past 15 years, the tourism budget of local governments outside the seven metropolitan cities and the capital region has more than doubled, from 1.3 trillion KRW in 2008 to 2.7 trillion KRW in 2023. Looking at this by region, the changes are even more pronounced. In Namwon, for example, the tourism budget, which was only 3.5 billion KRW in 2008, surged to 46.5 billion KRW in 2023, more than thirteen times. Similarly, Sangju’s budget rose from 6.2 billion to 16.9 billion KRW, Yeongju’s from 7.5 billion to 12 billion KRW, Gimje’s from 6.5 billion to 12.9 billion KRW, and Miryang’s from 1 billion to 19.4 billion KRW. In many cases, increased budgets are spent on the operation and promotion of local festivals. For instance, Hongcheon in Gangwon-do hosts six festivals annually. These include the Wild Edible Greens Festival in May, the Waxy Corn Festival in July, the Beer Festival in August, the Ginseng · Korean Beef Festival in October, the Apple Festival in November, and the Trout Festival in January. Some last as short a period as three days, while others go on for up to 15 days. Such temporary events are taking place competitively across mid-size cities nationwide. According to statistics from the Korea Tourism Organization (KTO), 783 festivals are held annually in regions outside the capital and major urban areas. Considering the duration of these festivals, this means that, on average, around 15 festivals coincide each day, with as many as 40 festivals happening on any given day. As a result, the budget for advertising, public relations, and marketing aimed at promoting these festivals has been steadily increasing. Comparing 2010 with 2024, Sangju’s marketing budget increased from 140 million to 1.68 billion KRW, Yeongju’s from 160 million to 510 million KRW, Yeongcheon’s from 10 million to 190 million KRW, Jecheon’s from 480 million to 890 million KRW, and Miryang’s from 350 million to 1.03 billion KRW.

Changes in tourism budgets of local governments in mid-size cities and the central government (2008 – 2023, data source: Local Finance Integrated Open System, Open Fiscal Data System)

Annual number of local festivals held in mid-size cities (2017 – 2025, data source: Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism)

Peak and Off-Peak Seasons

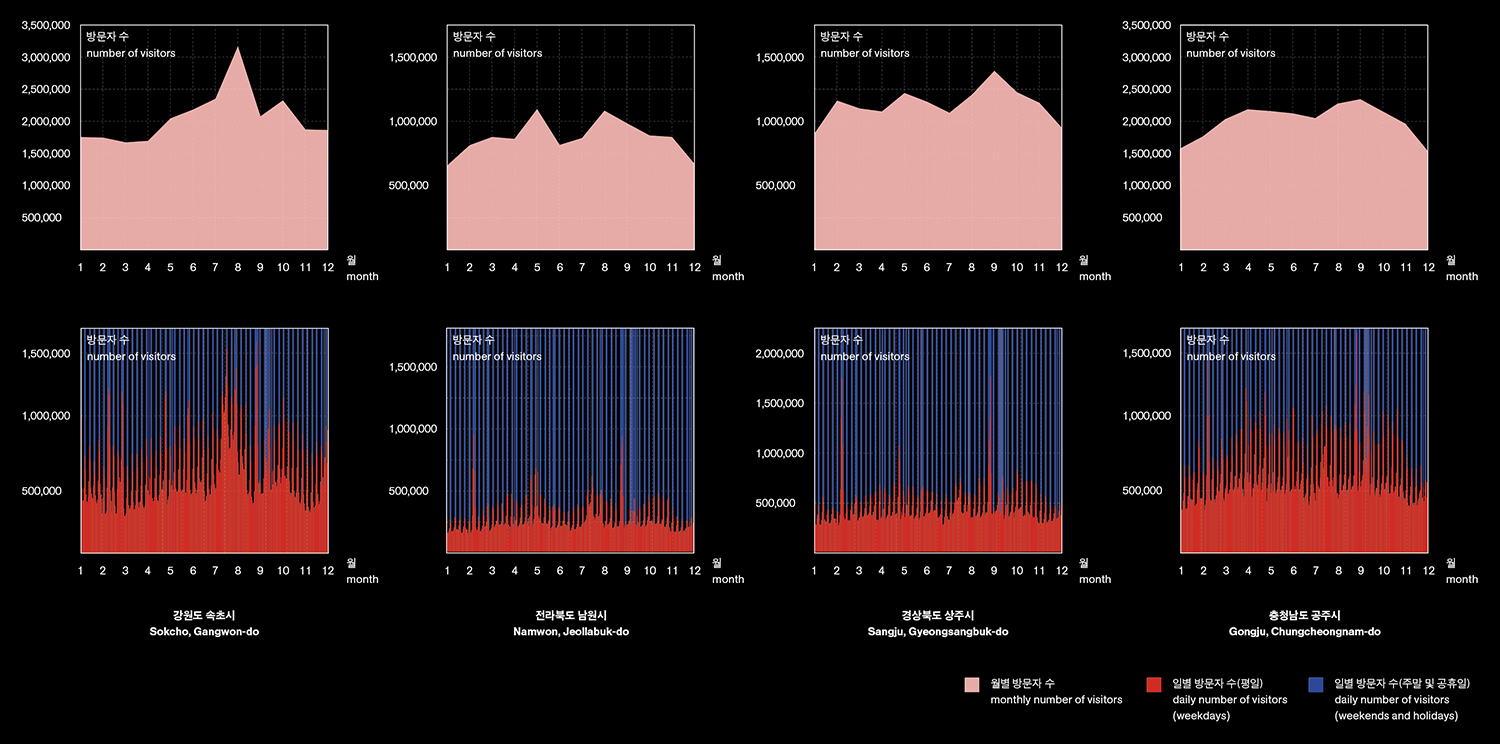

As tourism becomes a major economic activity in mid-size cities, the gap between the peak and off-peak seasons has become increasingly evident in their landscapes. An analysis of data from the KTO reveals an apparent seasonal fluctuation in most mid-size cities across the country. In Namwon, for example, the number of tourists on weekends in May and August is approximately 6.6 times greater than the number of weekday tourists in December and January. Other mid-size cities, such as Sokcho (5.7 times), Sangju (6.5 times), Yeongju (6.6 times), Yeongcheon (6.9 times), and Gongju (5.2 times), also display seasonal variations of over five times. These seasonal fluctuations bring about significant changes in the daily life of these cities. During specific periods, an influx of visitors arrives all at once, creating a peak time. At this point, the service demand reaches its zenith, and parking problems exceed critical levels, causing extreme congestion. Once that period has passed, the visitors leave just as quickly, and the city returns to a quieter state. This cycle of activity, where the city is only activated for a set period and remains devoid of people at other times, is a recurring pattern. This volatility can also be observed in the traditional or fifth-day markets, which have remained a long-standing feature of mid-size cities. On market days, people from surrounding rural areas flock to the city, only to disperse again once the market closes. However, as the local population declines and dependence on the tourism industry grows, the traditional role of the market as a space for local trade has expanded beyond its original purpose. It now serves as a cultural consumption space targeted at external tourists. Some fifth-day markets have even moved their dates to the weekend to align with tourist demand, incorporating various entertainment elements to attract visitors. As a result, the population disparity between weekdays and weekends in mid-size cities has grown considerably.

The rapid volatility of mid-size cities is leading to fundamental changes in urban systems. There is a growing need for temporary labour to accommodate the sudden influx of people from outside, as well as incentives to attract them and facilities for temporary housing. Additionally, as the tourism industry expands and mobility becomes more critical, there is an increasing demand for temporary parking spaces to handle surges in parking needs during specific periods. In this way, the concept of ‘temporality’, which has infiltrated mid-size cities on multiple levels, is causing a fracture in the traditional notion of the local community, which has long been based on strong bonds and a sense of belonging formed over time in a single place. Given the reality of an ageing population and a decline in population, increasing volatility and the various forms of temporality it creates are becoming defining characteristics of the declining mid-size city. Based on this foundation, if one were to conceptualise a new urban model, it would lead to a conclusion different from the ‘compact city’ model, which is based on urban concentration and permanent vitality. What is now required is the imagination of a new urban model in a more fluid and dispersed form—one that responds elastically to rapid volatility and temporality.

Monthly and daily visitor numbers in major mid-size cities in 2024 (data source: Korea Tourism Organization Data Lab). There are significant peak-off-peak seasons and weekdays-weekends variations.

The Other Side of the Peak Season

As previously explained, the gap between peak and off-peak seasons is most noticeable in the parking systems of mid-size cities and the short-term staffing structures needed to accommodate the influx of tourists. In cities already suffering from chronic parking shortages, the surge in vehicle numbers caused by specific events exacerbates the parking crisis. Local governments are attempting to address this by purchasing land to build parking towers or offering tax incentives to landowners to expand parking spaces. However, this leads to another urban side effect. The parking spaces created to meet peak season demand are often left empty and unused once the off-peak season begins. These unused periods last far longer than when they are actively used as parking spaces.▼2 Moreover, the introduction of temporary workers brings the need for temporary housing facilities, thus creating a new housing environment within mid-size cities that deserves attention. Securing short-term labour is becoming difficult due to ageing populations and population decline, so foreign workers are increasingly filling the gap (covered in SPACE No. 687). At the same time, the national trend of increasing foreign student recruitment is intersecting with local economic systems, resulting in an interesting new economic framework for mid-size cities. Sokcho in Gangwon-do is an extreme example of this phenomenon. In the next issue, we will examine the flexible changes in temporary labour, housing, and parking spaces in Sokcho and discuss how these changes affect urban space.

_

1 A comparison of the past and present streetscapes of buildings over three stories in the old town reveals an apparent transformation of the city into a low-density environment. Until 2010, every floor of buildings in the old town of Namwon was filled with various programmes and functions, but now, most of the upper floors, excluding the first and second, are vacant. Recently, even those on the first and second floors have begun to vacate. Although the physical structure of the buildings remains unchanged, their contents have disappeared, leaving the old town unable to sustain the same urban vitality it once had. For a more detailed examination of the thinning urban concentration, covered in SPACE No. 677.

2 The usage patterns of vacant lots in mid-size cities and new strategies for using them have been explored in detail in SPACE No. 680, ‘Urban Perforation’, and No. 681, ‘Erasing Plan’.

(top) Comparison of the past polycentric transport system (data source: Ministry of Construction, National Traffic Volume Map: National Traffic Survey Report Appendix, 1986) and the current monocentric system centred on the metropolitan area (intercity bus flow analysis, data source: Korea Transport Database). The strengthened connectivity between the metropolitan and regional cities is evident. (bottom) Comparison of past and present nationwide isochrone maps (data source: Ministry of Construction, Comprehensive National Territorial Development Plan, 1967). These maps illustrate travel times from Seoul to various regions. With the expansion of the national highway network, overall travel time has significantly decreased.