SPACE April 2025 (No. 689)

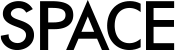

Roof structure and skylights

LLDS (co-principals, David Leggett, Paul Loh) is a studio that explores sustainable architecture by combining digital fabrication technologies with a handcrafted sensibility. In contrast to the often monotonous appearance of passive houses, Northcote House, designed by LLDS, boldly communicates an expressive form. This striking visual identity was fabricated and constructed in-house, using the studio’s own techniques. For LLDS, fabrication is an extension of design, allowing them to realise unconventional forms beyond standard production specifications without compromise, leveraging expertise gained through experimental prototyping. In this interview, David Leggett and Paul Loh discussed their vision for architectural sustainability and technological innovation, with a focus on Northcote House.

Front view of Northcote House

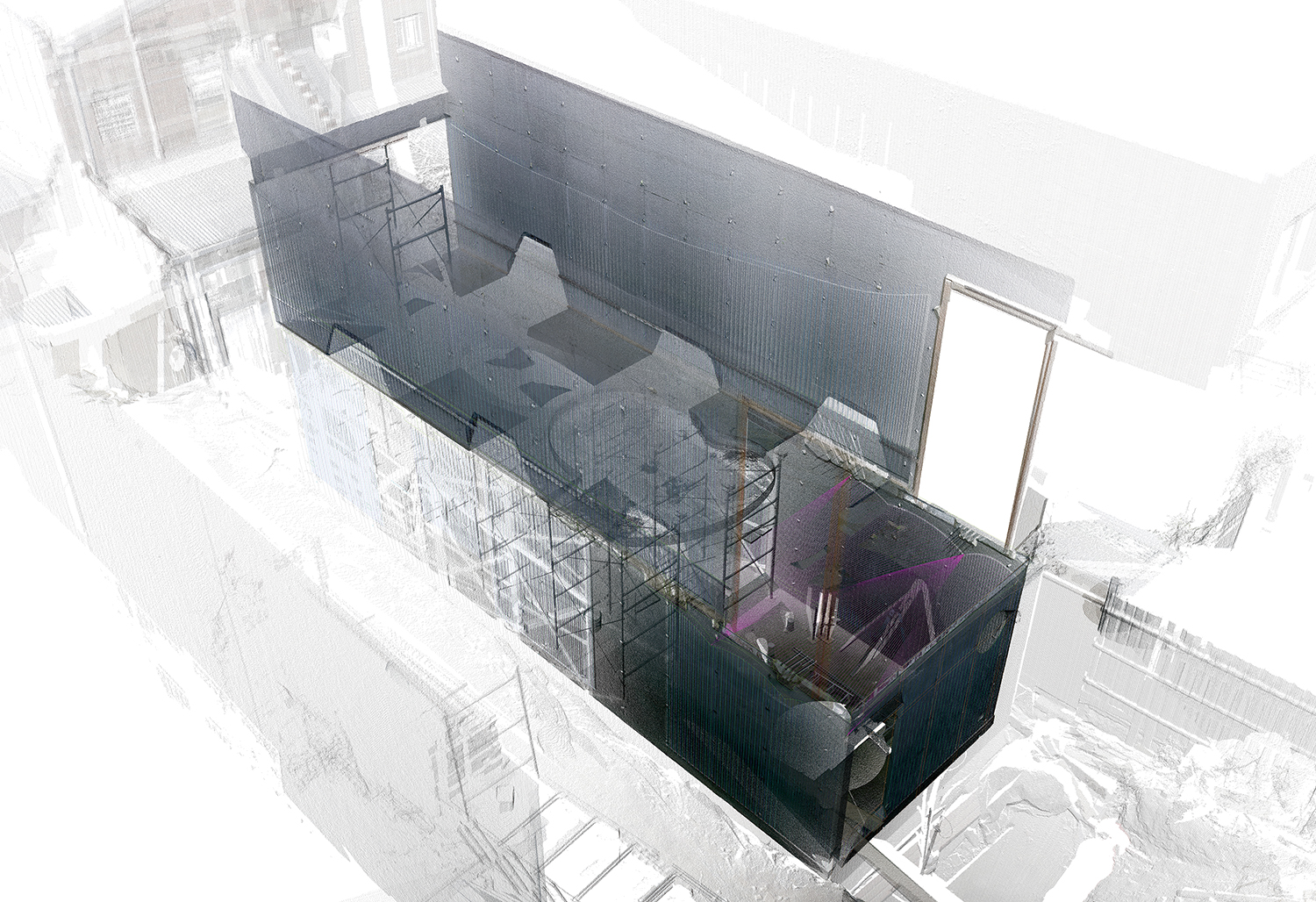

Mouth-blown glass

Lee Sowoon (Lee): LLDS is a team uniquely composed of architects, designers, researchers, and makers. It also has an in-house manufacturing facility. What brought about this fusion of project partners?

Paul Loh (Loh): The composition of our office is a reaction to conditions encountered in our present-day construction industry, where the practice of architecture is bound to the drawing board and rarely includes advanced manufacturing knowledge and research in design strategy. When we started the practice, we set up a workshop with a CNC router and industrial robotic arm alongside the studio. This allowed us to create prototypes in partnership with our design process, devising highly crafted architectural components. We use the prototyping process to simulate construction sequences to understand the process so we can adjust them to work for our design. Because of these needs, our team has built up a broad knowledge of digital fabrication, material understanding and experimentation.

Lee: Using digital fabrication technology, LLDS directly manufactures various kinds of architectural components such as the façade, staircase, and interior joinery. You also develop new construction techniques. How do you define the scope of your work?

David Leggett (Leggett): We don’t see ourselves limited to a particular scope in our work. This is one of the advantages of an advanced manufacturing system. Robotic and CNC manufacturing tools allow us to make various components and, therefore, do not limit us to a particular way of working.

Loh: Research projects feed our design process to create material knowledge; sometimes, a project is born out of it. Some research projects take off, like the PAM▼1 technology is now licensed to a new start-up company called Curvecrete. The PAM technology started as a workshop experiment when we were playing around with bending plywood; the idea was used to design the doubly-curved soffit of the Northcote House. These ideas, which sit behind research and built projects, are interconnected.

Lee: Northcote House incorporates various playfully shaped components. A massive timber roof structure serves as a key design element that defines the façade, but what role does it play in shaping the interior environment and spatial experience?

Leggett: Northcote House is a compact urban residence that re-conceptualises the Victorian residential terrace.▼2 The strong parallel boundary wall defines the terrace typology. It means that we have restricted light from the north and south. When reconsidering this typology, we used the roof as our third elevation—it houses the garden and draws daylight into the heart of the house.

Loh: This is a roof project. It creates a dramatic and atmospheric interior through the shafts of daylight that penetrate the house. The roof is not flat. Instead, it is sculpted with a thickness ranging from 200mm to 3m at its centre. The depth allows us to block out the harshness of the Australian sun and diffuse daylight across 13 skylights. Each of the skylights is lined with brass; when the light hits them, they glow and appear to float in space. All the other architectural elements work to accentuate the roof; for example, the staircase draws light down into the snug (the living space). The sculptural form creates a chiaroscuro effect across the surfaces, creating vivid shadows. You can see the interior as an exercise in playing with shadow and light. The same can be said of the concrete walls, which are pleated. The pleating allows sound to disperse, so it reduces echo in the space—it also creates a subtle gradation in shadow towards the heart of the house.

Textured concrete wall and the vaulted ceiling

Freeform curved railing

Lee: You sought to design a residence that would contribute to its urban surroundings. What strategy did you use to pursue this?

Leggett: We created the front and rear elevations like a trellis▼3 so our neighbour’s plants could climb over the garden’s boundaries—it makes the house look like it has always been there. The biggest contribution is the roof garden, of course.

Loh: The roof was originally designed to be a green roof, heavily planted. We changed our mind towards the end of the project to let it become a brown roof because our attitude towards nature changed. A green roof signals a garden for the occupants, but a brown roof is a garden for local wildlife and insects. The façade of the house already tries to render nature as synthetic by creating an infrastructure that allows climbers to take over the elevation, and we thought the brown roof would be our opportunity to give back to the ecology on the site. As it’s a brown roof, it only needs to be maintained once a year. We maintained it slightly more often at the start to stop some species from overtaking the roof and allow more native species to thrive. Nature is very good at controlling itself, and we just need to lend it a hand.

Lee: Northcote House advocates sustainable design through tectonic expression. Beyond the ecological benefits of the roof and the façade greening discussed earlier, what other environmental advantages does it offer?

Leggett: The key ones are as follows. First, material reuse: instead of conventional plywood or timber formwork, we used reusable formwork (PERI system) for concrete casting. PIR sheets were used as formliners and later cleaned and repurposed as roof insulation. We also ensured that only materials with a natural finish were used—no paint was applied anywhere in the house, eliminating the need for annual maintenance. The house is designed to be airtight, preventing heat loss. Instead of relying on an air-conditioning system, it employs passive cooling by leveraging the thermal mass of the concrete structure.

Lee: Aside from the concrete boundary wall, the interior wall, steel exterior wall, and roof structure were all specifically designed so that they can be dismantled or modified in the future.

Leggett: We need to consider how to ensure our buildings last longer than 10 or 20 years. We chose to use concrete as the primary structural material because we wanted a solid structure and everything else can be designed for disassembly in the future. Lifestyle changes, and so we can remove parts of the balustrade and install a lift, for example. The roof structure can be disassembled if there is a need to extend above.

Second floor interior

Lee: The majority of the architectural components were manufactured in a location less than 5km away from the building site. Is close collaboration with local architectural industry a priority for LLDS?

Leggett: For us, it is an important contextual point. Melbourne has a very active small to medium-sized manufacturing industry; partly because of our distance from the rest of the world, many skills still exist in the city.

Loh: We also have a very active craft industry, so we decided to commission the artist Ruth Allen to make a mouth-blown glass for one of the windows; it’s the only piece of pure craft object in the house that is not touched by machine or computer.

Lee: You even directly constructed the complex interior forms. How were the textured concrete finishes and the vaulted ceiling in the bedroom achieved?

Leggett: A PIR sheet was CNC-milled and added as a formliner inside the formwork to create the pleated texture of the concrete wall. The texture was developed after we created about 20 prototypes using different router tool profiles as the generator for the design. Each iteration allowed us to test what was feasible as some profiles created very poor finishes – they were either too fine or had undercutting▼4 – under-cutting makes it impossible to remove the formliner from the mould. The final pattern is the result of the tool profile (we use a V-shape cutter); for the tool path of the machine, we used a very simple set of parallel lines with a variable Z-dimension—the outcome is the pleated pattern that looks like fabric. The MDF mould was used to create the vaulted room in the east bedroom. This had to be robotically milled to create the three-dimensional form. It is constructed in layers so it can be safely disassembled from below after the concrete cures.

Loh: Our way of working is like a traditional craftsperson, except that all of our skills and techniques are accelerated by technology.

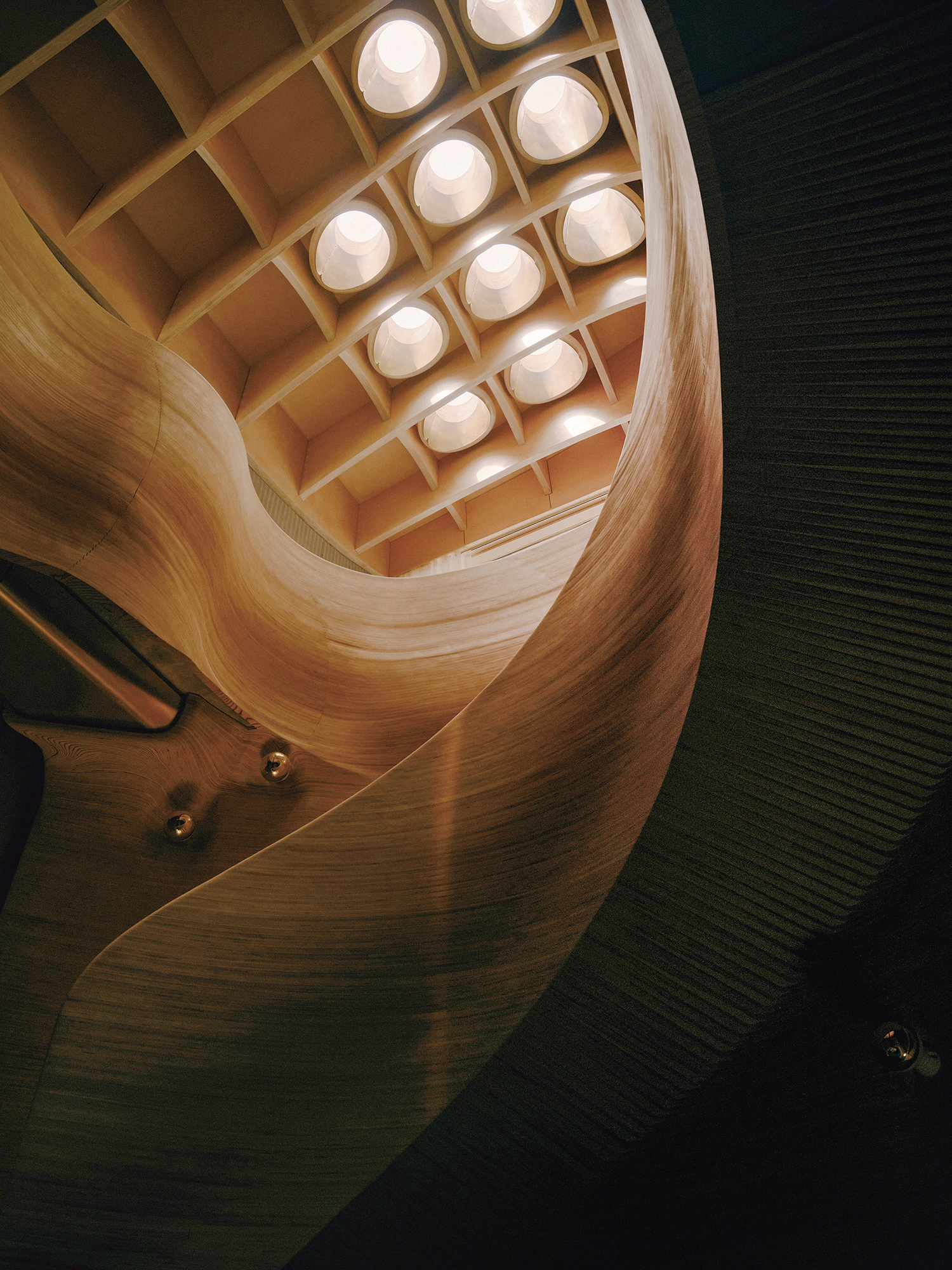

Lee: Advanced technologies were actively used to enhance precision in the construction process. What roles did point cloud scanning▼5 and AR (Augmented Reality) technology serve?

Loh: We took over 25-point cloud scans across the four-year build. This scanning process served two primary roles. First, it allows us to tailor the parts to the site conditions. When we have a complex junction, the point cloud allows us to precisely measure the actual building's form and adjust the digital model to ensure a perfect fit. The staircase is a good example of this. Second, to provide design feedback during the construction process. This means taking the site’s as-built data and translating it to influence or manipulate the design. For the concrete wall, we scanned after the second pour to measure where creep occurred in the formwork. This allows us to take the constructed pleated surface and match it with our digital model. We adjusted the digital model before we manufactured the next batch of formliners. By doing this, we ensured that the pattern of the first and second pours matched closely.

Leggett: We used a HoloLens▼6 with Fologram▼7 to manufacture the external trellis. Each pipe is hand bent using a standard hydraulic pipe bender—AR allowed us to take on super vision, so we can bend the pipe accurately to the digital model. For us, exploring advanced technology allowed us to overcome issues of budget and skill shortages.

AR fabrication. The QR code aligns the model being projected within the Hololens so it overlays over the pipe. ©LLDS

Transporting prefabricated components from the in-house manufacturing facility, Power to Make ©LLDS

Importing point cloud scan data of the as-built walls into 3D modeling software to adjust toolpath lines ©LLDS

Lee: How can the components of Northcote House be applied to larger-scale spaces or projects?

Leggett: The houses we designed are prototypes—prototypes of spatial ideas, construction processes and aesthetics. They are scalable, as we don’t think of them as components. Instead, we think of them as processes that can be expanded or applied to larger-scale projects; the spatial effect can multiply, and it may be different. The design and computational workflow are integrated so we can extend them or modify them for another project. For example, we are now designing another iteration of the roof structure, which is three times the size.

Lee: It appears that in today’s architectural world, sustainability is no longer considered as a critical concept but as a given. Now that sustainability is being taken for granted as an architect’s obligation, it feels trite to raise discussions on sustainability. Northcote House, however, distinguishes itself in that while featuring an outstanding sculptural outlook, its individual components that are designed to insulate, support loads, and improve acoustics are also all manufactured in an environmentally astute way.

Leggett: We see sustainability as a holistic approach to design. Our approach is from the material and construction perspective, as that’s what architects do best; it’s fundamentally our medium. To only practice sustainability as an idea is to treat sustainability as another ingredient; it will always read like a third wheel, or worse, added on. We need to reconsider sustainability from the conceptual, spatial and material perspective. Northcote House is our attempt to do this.

Loh: Our practice is interested in how we engender care within architecture and its construction. The word ‘care’ applies to how we build with our limited resources. We need to reconsider the construction process and procedure in relation to advanced technology to regain some control over our profession; the sense of control refers to control at the material and informatic levels.

Lee: What’s next for LLDS?

Loh: We will publish a book on Northcote House this year, in which we will share details of the design process and techniques, together with detailed outlines of the spatial concept. We call the book a manual—the idea is that it can be used or be accessible to others. Most people, and certainly students, think of digital fabrication and parametric design as form for form’s sake – too much technology with little soul – and the tool does not apply to more contemporary issues of inhabitation, waste and production. We think of the opposite—that architects could leverage their skills and ability, together with the rise of AI, to address the issue that concerns us most: sustainability.

1 Parametric Adjustable Mould (PAM). A technology patented in 2018 for manufacturing double-curved surface panels using a single CNC-formed mould.

2 An urban high-density housing type built in a continuous row along the street. Northcote House maintains the space-efficient approach suited to a narrow and elongated site while being constructed as a standalone structure without shared walls.

3 A lattice frame designed to support climbing plants.

4 A phenomenon in CNC milling or router processing where certain areas become inaccessible to the cutting tool.

5 A technology that captures the geometry of a 3D space as millions of spatial data points, generating a digital point cloud.

6 A Mixed Reality (MR) headset developed by Microsoft.

7 A software that uses MR devices like HoloLens and smartphones to visualise digital models.

Rear view of Northcote House

Overall view of Northcote House